Carbon-not Education & Ambassador Workshop Blog

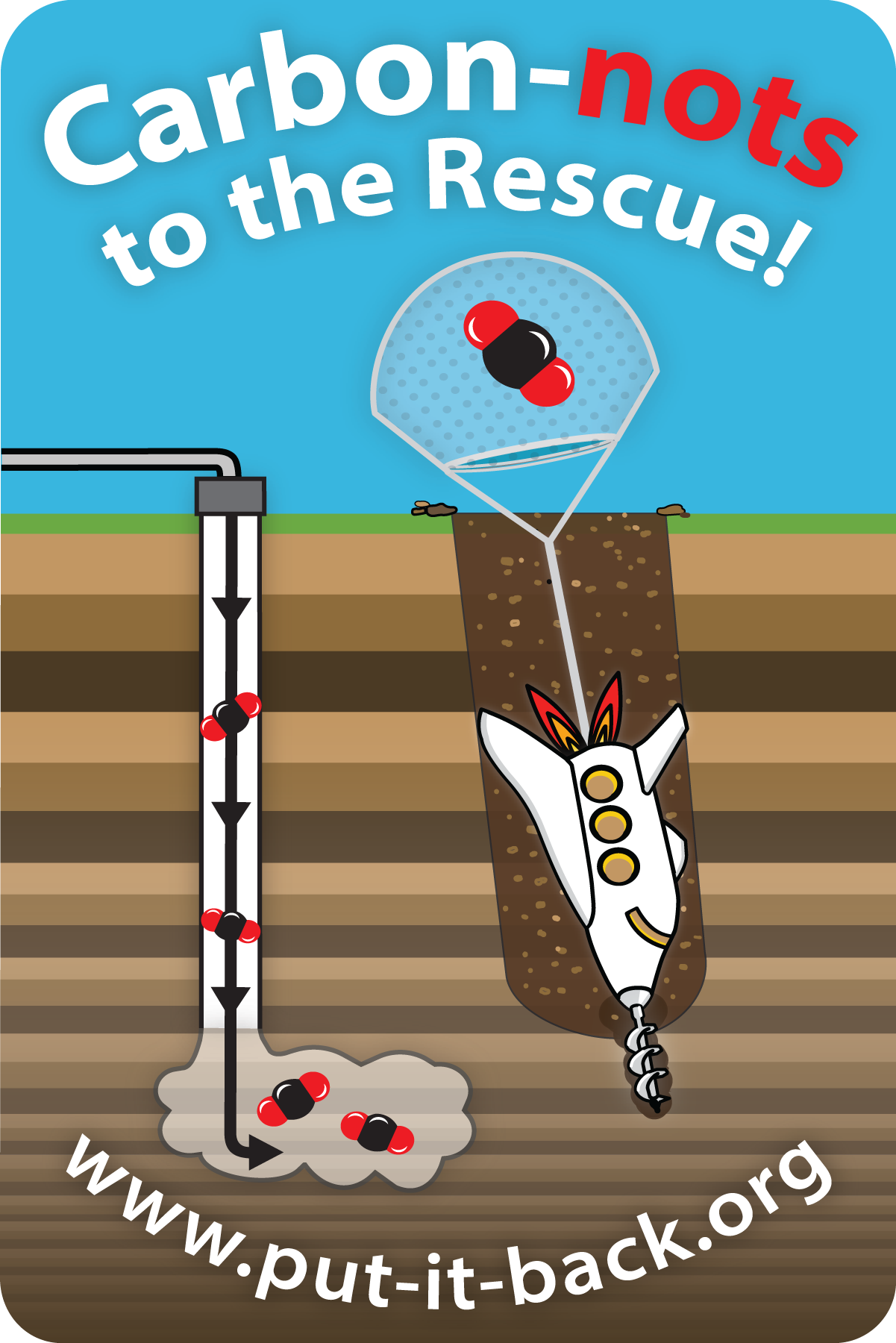

As CCS projects develop in the U.S. Gulf Coast area, community members must have many reliable sources of information to gain a better understanding of the technologies emerging in their area. As part of TXLA CMC activities, this workshop offered educational outreach by providing middle school teachers the CCS knowledge that may be implemented in classrooms and shared with the public. Ground-zero educators considered the integration of CCS topics into their classrooms to introduce the next generation of students to cutting-edge environmental science and technologies. The following webpage summarizes this 2024 workshop and resources specifically built for middle school teachers. Would you like to become a Carbon-not Ambassador? Sign up here.

Day 1

On Monday, July 15, 2024, the first Carbon-not Ambassadors, three dedicated middle school teachers from Corpus Christi, Fort Bend, and Cleveland, Texas, arrived in Austin. They gathered at the Gulf Coast Carbon Center at UT Austin’s Bureau of Economic Geology to explore the world of carbon capture and storage (CCS), including the carbon cycle, strategies to mitigate carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, and potential impacts of CO2 leakages from storage sites.

During Day 1, presenters and the middle school teachers discussed the effects of CO2 on the planet and experimented with dry ice to better conceptualize CO2, emphasizing that although something is invisible, it still exists. With demonstrations led by the GCCC’s Dr. Susan Hovorka, the group conducted a few experiments.

First, they used dry ice to show how CO2 can be observed by blowing bubbles over a container with dry ice, which releases CO2 (click here to see demonstration). Bubbles float normally through the air until they reach the CO2 layer within the container, where they float at a standstill, illustrating the density difference between air and CO2. This experiment makes the invisible presence of CO2 evident.

Next, they gathered air from the bottom of the container, which was mostly CO2, and poured the CO2 onto an open flame (click here to see demonstration). Although the gas is invisible, it smothers the flame, proving the presence of CO2. These hands-on experiments help make CO2 a tangible concept, with actual potential impacts on our lives, which leads to discussions of our relationship with CO2 on both small and global scales.

Our individual life choices impact carbon emissions, but at a larger scale, industrial processes contribute vast amounts, and they discussed various methods to address and reduce these emissions. Although switching energy sources and conserving energy are excellent options, CCS offers a vital mitigation solution that curbs current emissions.

The middle school teachers were equipped with resources and links to identify local emission sources in order to track upcoming CCS projects. Having these easily accessible sources online not only informs community members about local developments but also empowers teachers to pass on this knowledge to their students. This enables students to conduct their own research, quantify and calculate the emissions produced in their neighborhoods, and assess whether the local CCS projects are sufficient to offset those emissions.

They further discussed the GCCC’s research experience with CCS and focused on several major topics. First, they learned that CO2 storage, regulated under Class VI Underground Injection Program protocols set by the EPA, prioritizes the protection of the Underground Source of Drinking Water (USDW). Second, they highlighted the permanence of underground CO2 injection. Once injected, CO2 is challenging to recover due to capillary forces trapping the gas. This was demonstrated by a past GCCC project at the Frio site, where attempts to produce the injected CO2 were unsuccessful. Finally, we discussed potential risks and monitoring methods used to detect any issues that may arise.

As Class VI regulations prioritize the protection of USDWs, the remainder of the workshop was dedicated to groundwater monitoring and to understanding the impacts of CO2 in water.

Day 2

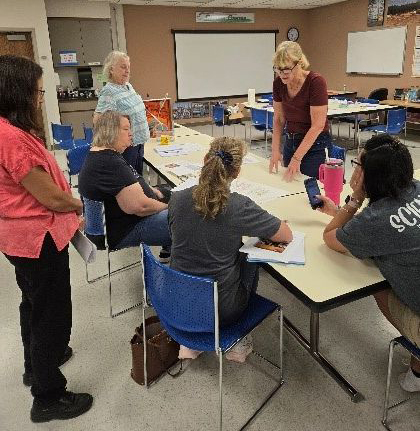

On Day 2 of this workshop, the GCCC focused on explaining the science and chemistry behind water testing as a method to detect the presence of CO2 in water. Dr. Katherine Romanak (in image standing on the right) discussed the critical role of CCS in combating climate change. Katherine also cited EPA’s stringent measures to protect underground sources of drinking water (USDW) when permitting Class VI wells for CO2 injection. Groundwater monitoring is a crucial requirement among the various monitoring tools for these permits, specifically mandated to detect any potential CO2 leaks into the aquifer.

The GCCC aims to equip teachers and students with the knowledge and tools to test for CO2 themselves, particularly if they live near a CCS project site. Our goal was to provide a practical, hands-on lab experience that could be easily conducted in the classroom, making the science of CCS both tangible and relevant to their everyday lives.

The middle school teachers learned that CO2 is not just a waste product; it is a natural component of all ecosystems. However, excessive amounts in the atmosphere pose a significant issue. Underground, CO2 is primarily produced by the respiration of roots and soil microbes, cycling among biotic and abiotic phases. When rainwater infiltrates the soil, it percolates into the soil and carries CO2 deeper into the aquifer through dissolution.

The dissolved CO2, interacting with water, forms carbonic acid (H2CO3), which disassociates based on the pH of the water. Most natural waters have a pH of between 6.5 and 8.5, resulting in most of the dissolved CO2 existing as bicarbonate (HCO3-). When calcium carbonate rock is present, this dissolution reaction causes the CO2 to weather the rock, buffering the pH and creating cations and bicarbonate, as shown in this reaction equation:

H2O + CaCO3 +CO2 ↔ 2HCO3- + 2Ca2+

Water + Limestone + Carbon Dioxide ↔ Bicarbonate + Calcium ions

In contrast, silicates do not react as easily, so pH is not as buffered, as would happen in a system that has carbonate.

So, using the equation listed, they tested the following key water parameters:

- pH

- Alkalinity

- Total Dissolved Solids

- Hardness

They tested these parameters on water flowing through two groundwater systems; one composed mostly of silicate rocks and the other of carbonate rocks. These systems were connected to a CO2 tank that provided a stream of gas into the water, allowing us to observe the changes in water chemistry over time.

As a team, the GCCC and middle school teachers plan to create a more student-friendly version of these laboratory experiments.

Day 3

On Day 3 of the workshop, the schedule was divided between (1) providing teachers with the opportunity to integrate CCS topics into the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) learning standards, and (2) visiting a water well site in south Austin.

Given that CCS topics can align with various TEKS, such as scientific investigation and reasoning, matter and energy, organisms and environments, and engineering, the Carbon-not Educators & Ambassadors drafted and prepared lesson plans tailored to their 7th and 8th grade classes. Additionally, they offered valuable insight as to how to further develop and expand this educational integration of CCS topics into the classroom for other interested teachers in Texas.

In the afternoon, the group visited a local water well to observe real-life water testing procedures. Justin Camp, a hydrogeologic technician from the Barton Springs Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, explained the crucial role that water conservation districts play in protecting aquifer and groundwater resources. He then demonstrated a common water sampling method using a bailer and a water-reading probe that checks for standard water test parameters.

Day 4

On the last day of the workshop, the teachers provided GCCC organizers with a list of the materials and support they need to effectively fit topics of CCS, the carbon cycle, climate-related phenomena, and groundwater protection into their classrooms’ curricula. These Carbon-not Educators & Ambassadors will help advise how other middle school teachers may teach these topics, knowing how this information fits into the TEKS.

The GCCC plans to support these teachers, who are attending CAST24 in San Antonio, TX on November 16, 2024. There, the Summer 2024 Carbon-not Educators & Ambassadors will host workshops and engage with other teachers in learning about how they can replicate the lab in their classrooms. Do you want to become a Carbon-not Educator & Ambassador? Would you like to make your students Carbon-nots? Sign up here.

Click here to download a copy of a CCS comic book that incorporates TEKS concepts.

2024 Carbon-not Ambassadors

Cynthia Hopkins

Corpus Christi Independent School District,

Nueces County

7th Grade Science & 8th Grade Engineering

Julia Dolive

Fort Bend Independent School District,

Fort Bend County

Advanced Academic Course (AAC) Science

Stephanie Hurst

Cleveland Independent School District

Liberty County

6th–8th Grade Science

Last Updated: July 23, 2025